New elements concerning the battle of Uxellodunum

The actual location of Uxellodunum, where the last major battle of the Gallic Wars took place in 51BC, generated early debates. But unlike other important places mentioned by Caesar, such as Gergovie and Alesia, the issue was still not settled even as recently as the year 2000, due to the lack of contemporary research at the site.

Moreover, one of the most serious contenders, Puy d'Issolud, on the banks of the Dordogne in the north of the department of Lot in what was the land of the Cadurcs, was in the 1990s subject to looting by users of metal detectors in particular at the Loulié spring - well-known since the nineteenth century as the source of a large amount of ancient weaponry. These two reasons were the source of the motivation to take over and finalise the records for this site.

On 26 avril 2001 in Toulouse, following the recent discoveries at the Loulié spring on Puy d'Issolud, the Ministry of Culture announced wih the key scientific experts of the period (including Christian Goudineau) that the site of Puy d'Issolud was that of Uxellodunum.

Moreover, one of the most serious contenders, Puy d'Issolud, on the banks of the Dordogne in the north of the department of Lot in what was the land of the Cadurcs, was in the 1990s subject to looting by users of metal detectors in particular at the Loulié spring - well-known since the nineteenth century as the source of a large amount of ancient weaponry. These two reasons were the source of the motivation to take over and finalise the records for this site.

On 26 avril 2001 in Toulouse, following the recent discoveries at the Loulié spring on Puy d'Issolud, the Ministry of Culture announced wih the key scientific experts of the period (including Christian Goudineau) that the site of Puy d'Issolud was that of Uxellodunum.

The quarrel of Uxellodunum

Historical data

Uxellodunum is the famous fortress where Gallic troops, including survivors of the siege of Alesia by Julius Caesar's legions, fought in 51 BC the last major battle, reported by Hirtius in Book VIII of the Gallic Wars.

Following the capitulation of Alesia in 52 BC and the defeat of the Pictones, massacred in the region of Lemonum (Poitiers) in spring 51 BC, the Senon Drappes, at the head of a band of "vagabonds" of 2000-5000 men was joined by the Cadurc Lucterios, a survivor of Alesia. They decided to invade Provincia. The Roman legate Caninius pursued them and just before he reached them they fled to the oppidum of Uxellodunum located in Cadurc country (later Quercy). When he arrived on the scene, Caninius established three camps on the heights around the oppidum and began construction of a retrenchment (countervallation) to surround it. Drappes and Lucterios established a camp 10 miles from the place. From there they could harass the Romans and rake the area to collect a maximum of provisions for the oppidum of Uxellodunum. But when Lucterios, having collected ample provisions, was leading a night convoy of wheat, it was intercepted by Caninius and put to flight. According to the information provided by the prisoners, Drappes camp suffered a surprise attack, his army was massacred and he himself was taken prisoner.

The Gallic troops, despite having lost their leaders, continued the fierce fighting and stood firm against Caninius and Fabius, who had arrived with reinforcements of two and a half legions. Caninius was obliged to report to Caesar who arrived against all odds with his cavalry followed by two legions of Calenus.

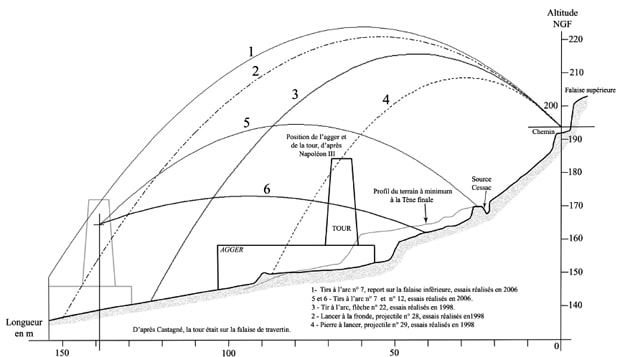

Finding that the fortification work conducted by the Roman troops completely surrounded the place, with no significant effect on the Gallic forces, Caesar decided to deprive them of water. Their access to the river was prevented by Roman war machines and near the spring that flowed at the foot of the ramparts he built an agger 18m high topped by a 10-storey tower (27m high) to prevent the Gauls getting water from the powerful source located on one of the flanks of the oppidum. At the same time, Caesar dug underground tunnels, out of sight of the defenders, to dry up the spring. Despite heavy fighting and burning the tower, the Romans reached their goal. The Gauls, deprived of water, believed the gods had abandoned them and they surrendered.

Caesar was ruthless. He ordered the hands of all those who had borne arms to be cut off, but spared their lives.

Uxellodunum est la célèbre place forte où des troupes gauloises, comprenant des rescapés d'Alésia, assiégées par les légions de Jules César, livrèrent en 51 av. J.-C. la dernière bataille importante, rapportée par Hirtius au livre VIII de la Guerre des Gaules.

Following the capitulation of Alesia in 52 BC and the defeat of the Pictones, massacred in the region of Lemonum (Poitiers) in spring 51 BC, the Senon Drappes, at the head of a band of "vagabonds" of 2000-5000 men was joined by the Cadurc Lucterios, a survivor of Alesia. They decided to invade Provincia. The Roman legate Caninius pursued them and just before he reached them they fled to the oppidum of Uxellodunum located in Cadurc country (later Quercy). When he arrived on the scene, Caninius established three camps on the heights around the oppidum and began construction of a retrenchment (countervallation) to surround it. Drappes and Lucterios established a camp 10 miles from the place. From there they could harass the Romans and rake the area to collect a maximum of provisions for the oppidum of Uxellodunum. But when Lucterios, having collected ample provisions, was leading a night convoy of wheat, it was intercepted by Caninius and put to flight. According to the information provided by the prisoners, Drappes camp suffered a surprise attack, his army was massacred and he himself was taken prisoner.

The Gallic troops, despite having lost their leaders, continued the fierce fighting and stood firm against Caninius and Fabius, who had arrived with reinforcements of two and a half legions. Caninius was obliged to report to Caesar who arrived against all odds with his cavalry followed by two legions of Calenus.

Finding that the fortification work conducted by the Roman troops completely surrounded the place, with no significant effect on the Gallic forces, Caesar decided to deprive them of water. Their access to the river was prevented by Roman war machines and near the spring that flowed at the foot of the ramparts he built an agger 18m high topped by a 10-storey tower (27m high) to prevent the Gauls getting water from the powerful source located on one of the flanks of the oppidum. At the same time, Caesar dug underground tunnels, out of sight of the defenders, to dry up the spring. Despite heavy fighting and burning the tower, the Romans reached their goal. The Gauls, deprived of water, believed the gods had abandoned them and they surrendered.

Caesar was ruthless. He ordered the hands of all those who had borne arms to be cut off, but spared their lives.

Uxellodunum est la célèbre place forte où des troupes gauloises, comprenant des rescapés d'Alésia, assiégées par les légions de Jules César, livrèrent en 51 av. J.-C. la dernière bataille importante, rapportée par Hirtius au livre VIII de la Guerre des Gaules.

The question of the location of the battle

A classic example of these political and military memoirs, both lively and tendentious, Caesar's Commentaries, which relate with admirable precision the different phases of the Gallic Wars, almost always give only vague and incomplete topographical descriptions of the places where action takes place. This state of affairs has generated many debates and controversies over their geographical location. The case of Uxellodunum has not escaped the rule, since its location turned in the 16th century in bickering twists, so much so that many sites claim the honour of having been Uxellodunum.

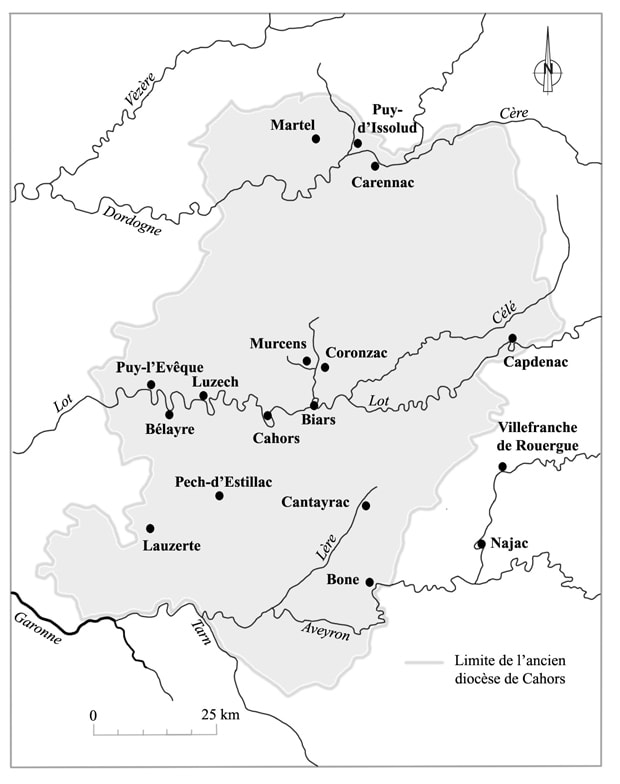

Apart from Puy d'Issolud, which has always had fervent supporters, authors have transported Uxellodunum to Carennac, Capdenac, Luzech, Cahors, Puy-l'Eveque, Murcens, Martel, Biars, Pech-d'Estillac near Castelnau-Montratier, Bélaye, Coronzac in Lot. But also among the most important candidates have been: Villefranche-de-Rouergue and Najac (Aveyron), Lauzerte, Cantayrac and Bonne (Tarn-et-Garonne), Uzerche and Ussel (Corrèze), Lusignan (Vienne), Bone Lacoste (Hérault ), Issoudun (Indre); and even Verdun-sur-Meuse, 800km from the territory of the Cadurques! Each author chose a location in his area and applied it with partiality to the Latin text!

Apart from Puy d'Issolud, which has always had fervent supporters, authors have transported Uxellodunum to Carennac, Capdenac, Luzech, Cahors, Puy-l'Eveque, Murcens, Martel, Biars, Pech-d'Estillac near Castelnau-Montratier, Bélaye, Coronzac in Lot. But also among the most important candidates have been: Villefranche-de-Rouergue and Najac (Aveyron), Lauzerte, Cantayrac and Bonne (Tarn-et-Garonne), Uzerche and Ussel (Corrèze), Lusignan (Vienne), Bone Lacoste (Hérault ), Issoudun (Indre); and even Verdun-sur-Meuse, 800km from the territory of the Cadurques! Each author chose a location in his area and applied it with partiality to the Latin text!

In the 18th century, the attribution of Uxellodunum to Puy d'Issolud was consecrated by the judgment of the scholar of Anville. It was called into question in 1819 by Jacques-Joseph Champollion-Figeac (brother of the famous Champollion, decipherer of hieroglyphs) who, after visiting these various localities and made excavations in Capdenac, supported the identity of Uxellodunum and Capdenac . He treated the question in a masterly way: "I will not open a career," he says, "but I will try to close it, and present a series of results that will remove all doubts, put an end to all the uncertainties, judge all the claims ". From then on, the attribution of Uxellodunum to Capdenac became official in the scholarly world!

Having resolved to write the life of Julius Caesar, the Emperor Napoleon III charged, in 1862, a commission to identify Uxellodunum. This one placed the oppidum in a loop of the Lot in front of Luzech, with the Pistoule.

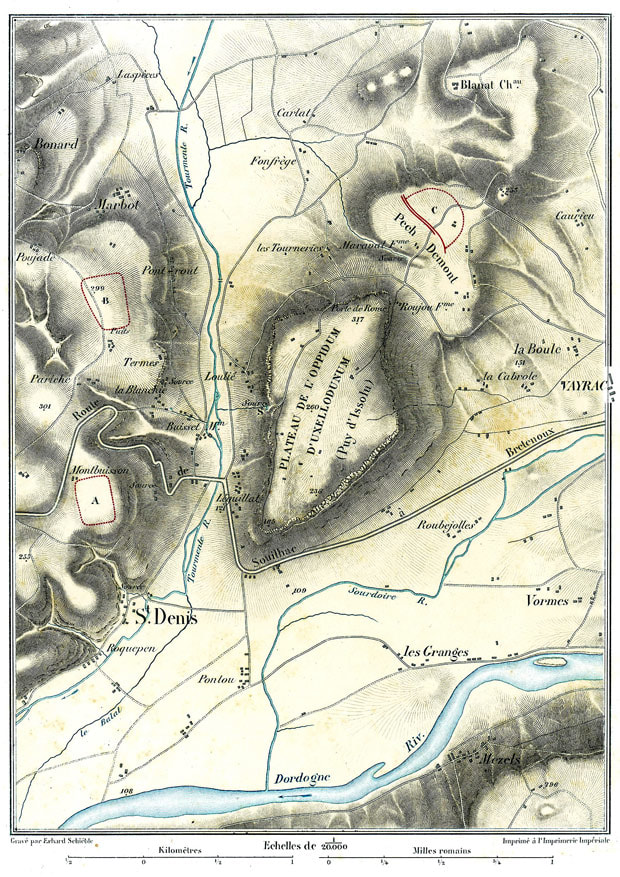

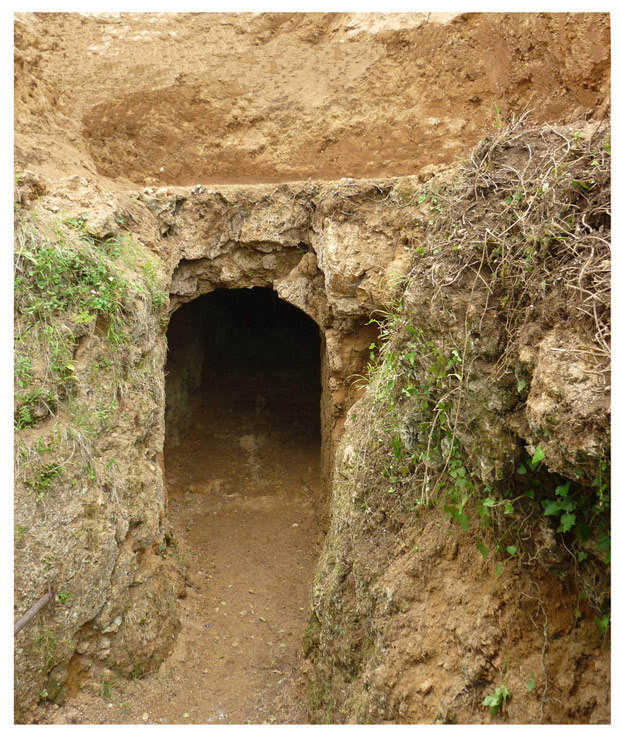

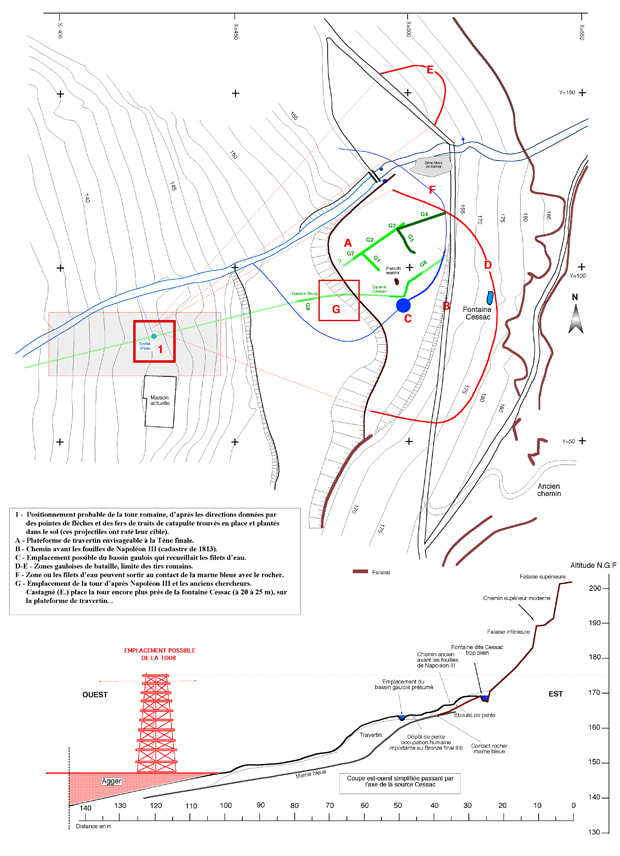

This site would have been definitively adopted, if Jean-Baptiste Cessac, originating from Souillac (Lot), had not protested against the official decision by sending several letters to Napoleon III and the publication of several brochures (1862-1865) . To confirm his opinion, he executed, from May 27, 1865, excavations at the fountain of Loulié. The discovery of some objects (catapult socket-shaped iron, arrow points socket, etc.), burnt stones, calcined earth, many charcoal, allowed him to obtain some funds from the General Council of the Lot. to continue the work, with the help of a commission chaired by the agent to see Etienne Castagné. On June 19, 1865, about 5 meters deep, J.-B. Cessac found an artificial gallery. This discovery caused a sensation. Napoleon III, informed by Cessac, sent two officers, Colonel Stoffel and Captain de Reffye, with a platoon of engineers, who continued the search. The Cessac gallery was cleared over 40 meters in length. The surroundings of the fountain were searched. The workers collected iron arrowheads, catapult horseshoes, many other objects, and framing nails at the alleged location of the agger (terrace built by Caesar). Near Pech-de-Mont, traces of countervallation and camps were discovered (Fig. 2).

In 1866 and 1874, E. Castagné published the report of the commission of the excavations. Following these results, Napoleon III, in his work on Caesar, declared that the battle of Uxellodunum had gone well at Puy d'Issolud.

After the Second Empire, purely literary polemics did not cease, and many articles continued to flood learned societies and the press and Uxellodunum was transported to many sites.

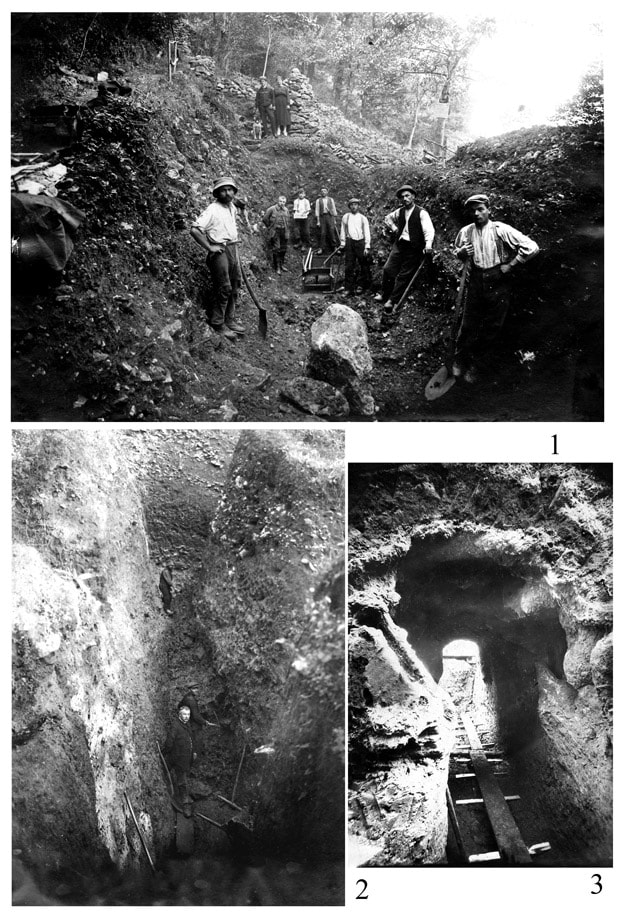

From 1913 to 1920, a teacher of Martel, Antoine Cazes, resumed the excavations around the fountain of Loulié, then, from 1920 to 1941, Antoine Laurent-Bruzy undertook at his expense new excavations at the fountain and, after 15 years of research, discovered a second so-called Roman gallery (Fig. 3-3). His death stopped his work. The many objects discovered during these twenty years had never been inventoried and only Armand Viré published details of part of the armament in 1935.

Having resolved to write the life of Julius Caesar, the Emperor Napoleon III charged, in 1862, a commission to identify Uxellodunum. This one placed the oppidum in a loop of the Lot in front of Luzech, with the Pistoule.

This site would have been definitively adopted, if Jean-Baptiste Cessac, originating from Souillac (Lot), had not protested against the official decision by sending several letters to Napoleon III and the publication of several brochures (1862-1865) . To confirm his opinion, he executed, from May 27, 1865, excavations at the fountain of Loulié. The discovery of some objects (catapult socket-shaped iron, arrow points socket, etc.), burnt stones, calcined earth, many charcoal, allowed him to obtain some funds from the General Council of the Lot. to continue the work, with the help of a commission chaired by the agent to see Etienne Castagné. On June 19, 1865, about 5 meters deep, J.-B. Cessac found an artificial gallery. This discovery caused a sensation. Napoleon III, informed by Cessac, sent two officers, Colonel Stoffel and Captain de Reffye, with a platoon of engineers, who continued the search. The Cessac gallery was cleared over 40 meters in length. The surroundings of the fountain were searched. The workers collected iron arrowheads, catapult horseshoes, many other objects, and framing nails at the alleged location of the agger (terrace built by Caesar). Near Pech-de-Mont, traces of countervallation and camps were discovered (Fig. 2).

In 1866 and 1874, E. Castagné published the report of the commission of the excavations. Following these results, Napoleon III, in his work on Caesar, declared that the battle of Uxellodunum had gone well at Puy d'Issolud.

After the Second Empire, purely literary polemics did not cease, and many articles continued to flood learned societies and the press and Uxellodunum was transported to many sites.

From 1913 to 1920, a teacher of Martel, Antoine Cazes, resumed the excavations around the fountain of Loulié, then, from 1920 to 1941, Antoine Laurent-Bruzy undertook at his expense new excavations at the fountain and, after 15 years of research, discovered a second so-called Roman gallery (Fig. 3-3). His death stopped his work. The many objects discovered during these twenty years had never been inventoried and only Armand Viré published details of part of the armament in 1935.

Fig. 3 - Excavations conducted by Antoine Laurent-Bruzy: 1 - Excavations of 1921-1922, at 12.5m downstream of the fountain. Under a large block were found human bones, Gallic arrows and two Roman catapult bolts. 2 - Trench research in 1925. At 4m from the Cessac gallery of 1865, 12m deep. 3 - Gallery found in 1935 by Laurent-Bruzy downstream of the Cessac gallery.

Le Puy d’Issolud

Geographical situation

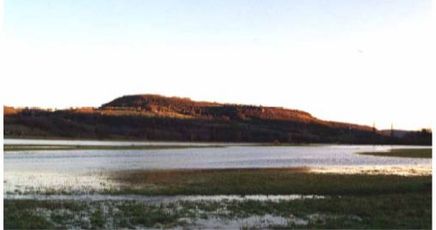

Puy d'Issolud is an geological outlier, separated from the causse of Martel by the valley of the Tourmente and from the causse of Gramat by the valley of the Dordogne. The plateau of approximately 80 hectares is situated mainly in the commune of Vayrac, with its western and south-western slopes in the commune of Saint-Denis-lès-Martel. Its highest point at 311m is in the north east, in the place known as "Lous Templés".

The plateau slopes down unevenly to the south-west to an altitude of 250m and, to the west, above the Loulié spring, to 210m. There are high, sheer limestone cliffs to the north-west and south. Elsewhere, the slopes and rocky outcrops are steep and often abrupt. To the north, a saddle joins Puy-d'Issolud to Pech-de-Mont (261m), the land sloping gently away on the north-west side towards the river Tourmente and to the south-east towards Vayrac.

To the north-west and west of the plateau, the Tourmente crosses the plain of Viane, or the Hierle, (115 m), an ancient marshland today occupied by meadows, which extends to the village of Quatre-Routes.

Despite regular drainage close to Saint-Michel-de-Bannières, this plain is flooded from time to time. Equally, to the south of Puy d'Issolud, the valley of the Sourdoire is frequently flooded up to Bétaille.

Before the construction of the railway line between the Tourmente and the bend of the Sourdoire, there was also a swampy and marshy area that prohibited any construction. When the waters of the Dordogne river are high, there is backflow into the waters of the Tourmente and the Sourdoire, which affects this area.

There are several springs on the slopes of the site but the only one that provides water regularly and in abundance is the Loulié spring (la Fontaine de Loulié), on the southwest flank at an average altitude of 163.50m .

The plateau slopes down unevenly to the south-west to an altitude of 250m and, to the west, above the Loulié spring, to 210m. There are high, sheer limestone cliffs to the north-west and south. Elsewhere, the slopes and rocky outcrops are steep and often abrupt. To the north, a saddle joins Puy-d'Issolud to Pech-de-Mont (261m), the land sloping gently away on the north-west side towards the river Tourmente and to the south-east towards Vayrac.

To the north-west and west of the plateau, the Tourmente crosses the plain of Viane, or the Hierle, (115 m), an ancient marshland today occupied by meadows, which extends to the village of Quatre-Routes.

Despite regular drainage close to Saint-Michel-de-Bannières, this plain is flooded from time to time. Equally, to the south of Puy d'Issolud, the valley of the Sourdoire is frequently flooded up to Bétaille.

Before the construction of the railway line between the Tourmente and the bend of the Sourdoire, there was also a swampy and marshy area that prohibited any construction. When the waters of the Dordogne river are high, there is backflow into the waters of the Tourmente and the Sourdoire, which affects this area.

There are several springs on the slopes of the site but the only one that provides water regularly and in abundance is the Loulié spring (la Fontaine de Loulié), on the southwest flank at an average altitude of 163.50m .

Historical records

The oldest document that identifies Puy d'Issolud at Uxellodunum is a highly contested (or apocryphal) act dating back to the 10th century. By a charter of 935, King Raoul donated to the abbey of Saint-Martin de Tulle a high place or mountain (podium) called Uxelloduno, located in Quercy near Vayrac where, according to a remark of six words in the act, was once a city known to have been besieged by the Romans. This geographical situation corresponds to the current Puy d'Issolud. The history of the document begins at the end of the sixteenth century, when by complicated paths it reaches the historian Justel who documents the contents in a book published in 1645.

On the other hand, three land titles dated 941, 944 and 945 relate to a domain called Exeleduno, which cannot be anything other than the Uxelloduno podium, the property ultimately passed on to the monastery of Saint-Martin-de-Tulle.

On the other hand, three land titles dated 941, 944 and 945 relate to a domain called Exeleduno, which cannot be anything other than the Uxelloduno podium, the property ultimately passed on to the monastery of Saint-Martin-de-Tulle.

Archeological context

The plateau of Puy d'Issolud has been inhabited since the Middle Paleolithic. Many remains of the Late Bronze Age and the end of the first Iron Age have been discovered. On the other hand, the occupation of the end of the second iron age is very poorly known. Etienne Castagné and Armand Viré described various earth movements and important dry stone walls that border the plateau at several points, interpreted as the remains of a rampart of this period, but no recent study has confirmed this interpretation or dating. In the middle of the 1st century AD the Gallo-Romans were installed there. There are also traces of the end of the Merovingian period.

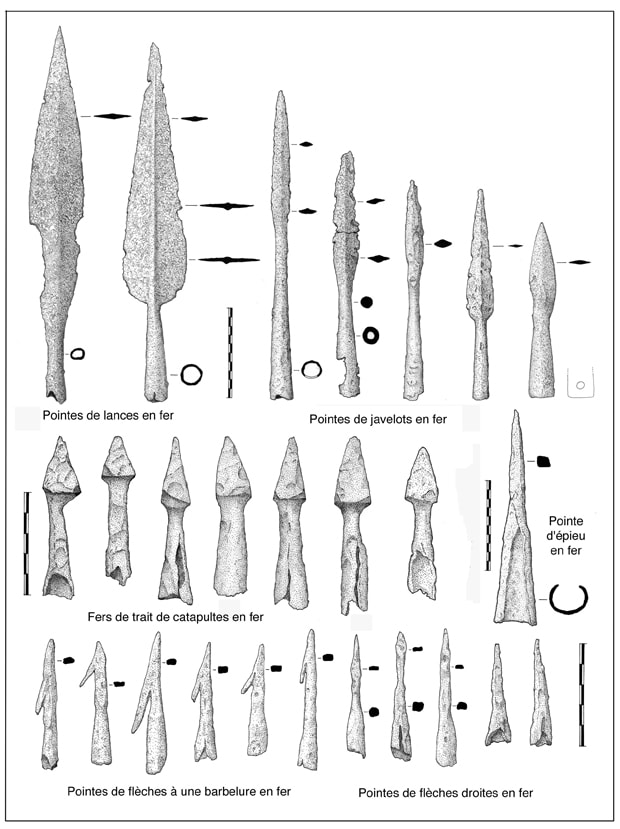

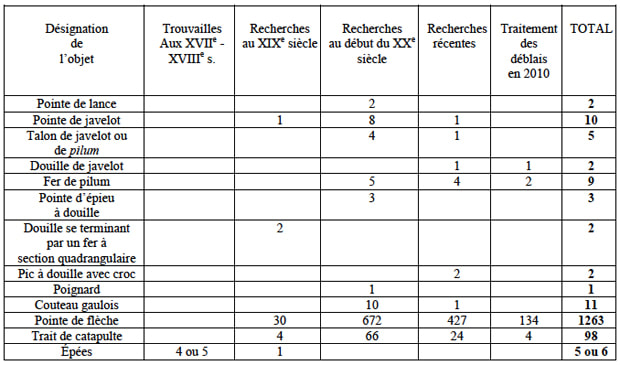

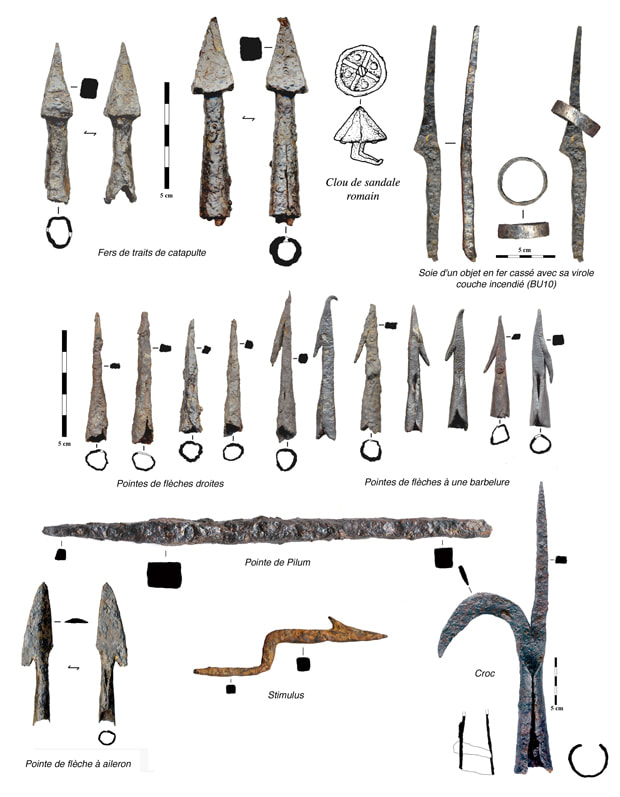

The sole purpose of the ancient excavations at the Loulié spring were to bring to light the tunnels dug to divert the source. No stratigraphy was recorded, and the only observations of the time were made by J.-B. Cessac, then by A. Viré. Several thousand cubic meters of material were moved, using shovels and pickaxes, without scientific investigation or recording. These excavations yielded vestiges of occupations of the Final Bronze Age and the Iron Age. But the impressive number of armaments found during these excavations (more than 700 arrowheads, 75 catapult lines, 6 javelin spikes, 2 spears, etc.) all from the age of Caesar, is particularly striking; they prove that this place was the theatre of a violent military confrontation in the middle of the 1st century BC.

Les nouvelles recherches à la fontaine de Loulié

From 1993 an ambitious research program was set up in the context of programmed annual and then multi-annual operations, authorized and financed by the French Ministry of Culture. It consisted of two main stages:

- From 1993 to 1996, research, census and exploitation of all documents on the question of Uxellodunum, followed by the production of an inventory, in collaboration with Pierre Billiant, of the many objects (of all periods) discovered on the Puy d'Issolud.

- From 1997, establishment of a multidisciplinary team made up of researchers from all walks of life - both volunteers and professionals - covering all the fields necessary for the study of the question - historians, archaeologists, hydrogeologists, specialists in the study of old civil engineering works, analysis laboratories for dating the finds... The field program was centred on the sector of the Loulié spring.

State of conservation of the site

The systematic analysis of old documents (photos and excavation notes) and the micro-topographic survey of the entire site confirmed that the area of the Loulié spring was deeply disturbed first by the Travertine quarries in use towards the end of the Middle Ages, second, by terraced vineyard cultivation in the 19th century and third, excavations of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Successive excavations had largely destroyed the site, with very deep trenches (from 6 to 12 meters deep) excavated generally east-west and north-south. However, we were able to find some islands of archaeological remains in place, and to which we gave the term "buttes", i.e. mounds, and identification in the form "BU" followed by a number.

|

On the upper terrace, generally between 1.50m and 2m of soil is missing. BU1 includes a layer of the 1st century BC with large blocks aligned and containing armaments. BU2 is a reference for the final Bronze IIIb and the first Iron Age. BU10 comprises a layer of the same nature as that of BU1, topped with a level of destruction of the same period. On the lower terrace, BU3 corresponds to a garden layout in the 16th century. BU4, surmounted by old excavations, has at its base a surface of Gaullic circulation with a hollow structure. BU5 to BU12 are piles of excavated material accumulated by the ancient excavations. |

The total area of ancient excavations, about 2300m2, has been analysed. Only 25m2 of layers dating from the 1st century BC were still in place before the research (BU1, BU4 and BU10). All the rest was destroyed by the quarrymen and the workers carrying out the ancient excavations.

Results of research

General topography of the sector of the spring

|

Surveys of the current topography, set against the analysis of the documentation (in particular the information on the ancient excavations) plus the geological and hydro-geological studies, made it possible to come close to defining the outline of the topography of the sector of the Loulié spring in the 1st century BC. Since the beginning of the Holocene a mass of travertine has gradually formed at the foot of the cliff of Puy d'Issolud, caused by the presence of a permanent, abundant spring at this location. This massif then experienced a succession of phases of erosion and accretion, caused by man-made impact on the surrounding environment. The mass, existed in the 1st century BC in the form of a shelf at the foot of the cliff. The shelf contained a series of natural basins filled with water, spread over an area of several hundred square meters, developed by man over time A cascading front allowed the basins to overflow. Archeological and geological studies have shown that this front advanced much more towards the valley than its present geometry suggests, since it is today greatly reduced by quarries and by both medieval and modern agricultural practices, by earthworks generated by the excavations of the nineteenth and early twentieth century and also by the mechanisms of erosion specific to this type of geological formation. The impact of erosion must be taken into account all the more because nothing in the first stratigraphic studies of the mass suggests that the phenomenon of accretion took place after the period of the second Iron Age. |

The basin located at the foot of the cliffs of the plateau cleared in 1865 by J.-B. Cessac then by Laurent-Bruzy in the 1920s and was considered then to be the water source used by the Gauls during the siege of Uxellodunum. However, it is in fact an overflow of lower sources according to the hydrogeological studies conducted by Jean-Paul Fabre. Currently, water flows for around 4 to 7 months of the year, usually between December and June. During the other months, the basin is dry or partially filled by rainwater coming in from the eastern side through fractures in the rock (Fig. 9).

The resumption of the excavation of this basin introduced several new elements. This natural hole, arising from three fractures in the rock, was summarily equipped with nine steps to enable a descent into it. Two steps are composed of large squared-off stones and the others are carved into the rock. The excavated infill consisted, up to the third step, of sludge mixed with plants, large blocks and small limestone elements from the east slope.

|

On the south-east side, at the level of a fracture, was a large deposit of fine clay. The archaeological remains here consist of three coins from the early 20th century and two modern shoe nails with round stems. Up to the last step, the infill was composed of large and medium blocks of limestone mixed with a clayey earth, containing a few small pieces of quartz gravel. Some contemporary furniture items have also been discovered there.

Basically, the infill consisted of a very clayey earth containing some small quartz gravels and very small calcareous elements. No archaeological element was found there. The notes left by J.-B. Cessac concerning his excavation of the sector confirm that he found no remnant of Iron Age or any other period in the basin itself. The few weapons he mentions in this sector come from the slopes on the periphery of this basin. All these elements lead to the conclusion that this basin is not a sustainable source and especially that it was probably not known in the Gallic period. The intersection of these two approaches makes it possible to affirm today that the "Cessac basin" can in no way be the water source evoked by Caesar's text and that, given the geometry of the travertine massif, the agger built by the Roman troops could not be as high on the slope of the site as Napoleon III thought. This agger must therefore be sought much lower. |

Archeological levels found in place

The occupation on the surface of the travertine massif

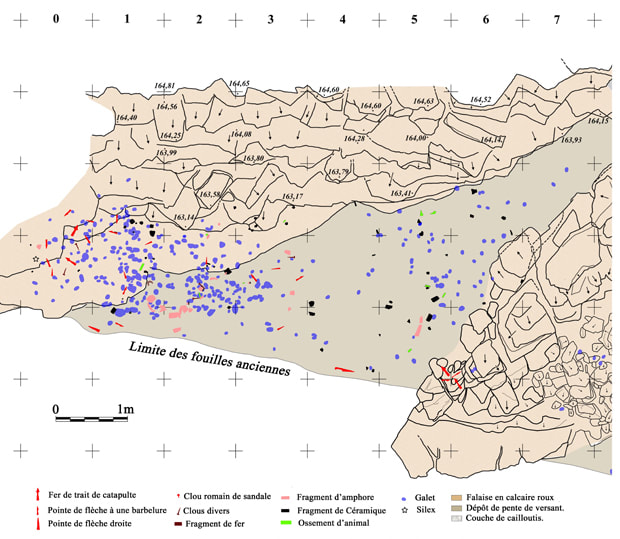

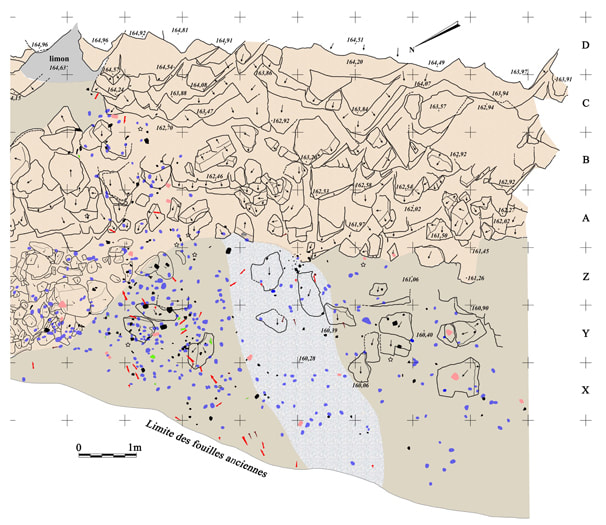

|

The main results in this area come from the excavation of the BU10 mound on a conserved surface of about 16 m2, which revealed a layer of destruction of a burned Gallic construction. The presence of reddened earth, charred logs and Roman armament made it possible to date this structure.

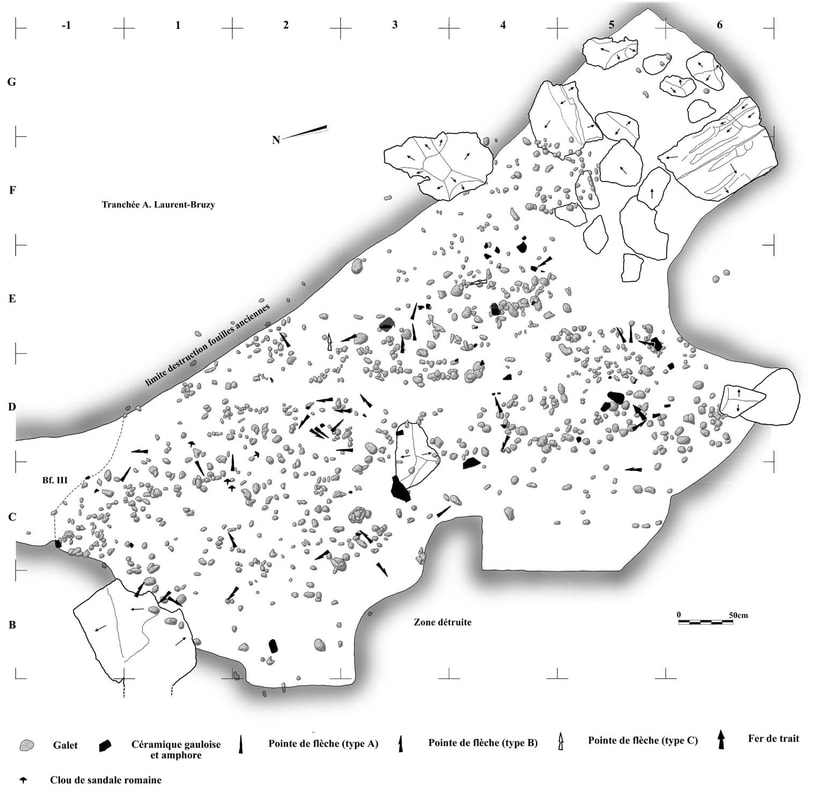

The research has highlighted three main steps. First of all, a 6.5 m wide excavation was made in the final Bronze layers, up to a natural scree on the slope. The old excavations have amputated this construction on its eastern and western flanks. The soil at the bottom of this excavation was very irregular; large blocks of natural scree are apparent. In its northern part, about 3 m wide, the ground is pretty much horizontal. To the south and south-east, it has a southwest-facing slope of about 20 °, while to the northwest it has a strong east-west slope. The numerous bronze fragments of the final Bronze IIIb present at the base of this construction are mostly crushed by trampling, thus confirming the existence of a floor of circulation; this one is strongly reddened under the action of fire; five ancient arrow heads had crossed the overlying layer to fuse into the Late Bronze layer. This reddened ground was covered with a layer approximately 10cm thick containing numerous objects, all of which have undergone the action of fire (Fig. 10):

|

On the surface of this layer were numerous fragments of charred oak logs. In their positions, the very compact and strongly rubefied soil was carbonised in places. The 14th century datings made on five of these logs yielded the following chronological calibrated ranges: -103 to +82; -86 to +76; -356 to -2; -85 to +67; -43 to +78. Two archeomagnetic analyses of the reddened soil yielded the following age ranges: -100 to +10; -100 to -5.

This layer was covered by a scree of thickness 0.35 to 0.60 m, completely reddened. About 4 m wide, it was made up of terracotta, bricks (originally moulded mud blocks) fired during the fire (2) and travertine rubble altered or converted to lime by the action of fire (Fig. 11). In its southern part, 1.60 m wide, the scree was mainly composed of reddened limestone, agglomerated by heat. But to the east, at the base of this area of stone, there were fragments of bricks (originally blocks of raw earth) and travertine blocks altered or converted into lime by the action of fire. Above this first scree, probably resulting from the collapse of an elevated structure, was another reddened scree, with a thickness of 0.15 to 0.25 m, consisting of medium and large limestone elements also altered by the action of fire. This layer is absent to the south. The archaeological elements of the upper scree consist of Dressel 1B amphora fragments, the bottom of the handle and the foot of a Lamboglia 2 amphora, small fragments of Gallic ceramics, and a tapered broken tang of rectangular section, with its ferrule. Almost all the elements that made up the two screes have a general east-west or north-east / south-west dip. Finally, to the south-east, we uncovered an accumulation of unreddened stone blocks that appear to be in place. |

Fig. 10 - Sector BU10, Gallic level. Implantation of pebbles, Gallic pottery, arrowheads, catapult bolts and roman sandal nails.

View of the ground of the destruction level, lying above the ground level of the Late Tene period; adobe bricks piled up and baked by fire which also reddened the surrounding earth.

Fig. 11 - Mound BU10, July 1998, north-west sector : Gallic layer showing destruction, strongly reddened, containing reddened fire-baked adobe blocks and blocks of travertine transformed into lime by the action of fire. Burnt oak logs can be seen at the front of the photo. The battleground is found underneath the burnt logs, on top of the mass of fallen rocks from the slope above.

|

Research in mound BU1 revealed an interrupted soil in the south lying against large blocks. The layer, 3 to 10 cm thick, that covered this ground contained 7 arrowheads and a catapult bolt. An arrow was planted in the ground. This layer contained 13 pieces of charcoal. Pottery was scarce and limited to about fifty small pieces made of native gray or beige clay and 38 Dressel 1 type amphora fragments, including a handle that is attributable to Dressel 1B. This layer was itself covered with a landslide of blocks. |

Work on mound BU4 revealed a small hearth with an undated cultural layer. Under this layer was a landslide of blocks that appeared to come from a collapsed dry stone building, which would have been located further east, or southeast. Under the blocks and above the travertine bedrock, the excavation revealed a cultural layer with a hollow, rounded structure (1.5m diameter to 1.1m depth). In this excavation and on its periphery, have been discovered artifacts attributable to the late Tene culture, without any more precision, in particular fragments of dressor 1 amphora belly and handle, of native gray clay pottery without particular character, and nails. No evidence of fire or armaments was found. |

Les pentes sous les falaises qui dominent la fontaine

To the south, (Figs. 12 and 13) a natural and widened cleft in the cliff has been developed by man for defensive purposes. Upstream and downstream of this, the excavation revealed, as for mound BU10, a soil and a layer of occupation surmounted by a scree, the set containing armament of cesarean period:

41 arrowheads,

9 catapult bolts,

a stimulus,

a tip of pilum,

a hook,

a knife,

Dressel 1/1B and Tarraconensis amphora fragments,

native pottery,

many pebbles.

The excavation carried out in 1927 by A. Laurent-Bruzy at the edge of this zone had already revealed a burned ground in a layer 0.2m thick, hundreds of arrowheads, catapult bolts, spears, numerous fragments of amphorae, nails, pottery and numerous pebbles. On this floor, three enormous stones had been unearthed and attributed to the wooden pillars of the right base of the Caesarean agger.

41 arrowheads,

9 catapult bolts,

a stimulus,

a tip of pilum,

a hook,

a knife,

Dressel 1/1B and Tarraconensis amphora fragments,

native pottery,

many pebbles.

The excavation carried out in 1927 by A. Laurent-Bruzy at the edge of this zone had already revealed a burned ground in a layer 0.2m thick, hundreds of arrowheads, catapult bolts, spears, numerous fragments of amphorae, nails, pottery and numerous pebbles. On this floor, three enormous stones had been unearthed and attributed to the wooden pillars of the right base of the Caesarean agger.

|

To the east, the presence of Dressel 1/1B amphora fragments and some Gallic pottery shards practically in contact with the substratum allows us to say that, at least in the first century BC, the landscape of the slopes under the cliffs was totally bare. The steepness of the slopes, of the order of 35° to 40° depending on the sector, prohibits any human occupation. No development has been identified in this area. The careful examination of these few "shreds" of archaeological layers in place and the artefacts they contained confirms two important points. There was indeed an occupation of the second Iron Age centred on the sector of the springs located on the mass of travertine at the foot of the cliffs; it is characterised by a layer and a level strongly burned by a violent fire, and delivering armaments in abundance and limited quantities of various pottery artefacts. These are clearly attributable to the 1st century BC. |

The armaments are in all respects similar in composition to those discovered in the ditches of Alesia or Gergovie and more widely on all sites of battles of the Caesarean period found in Gaul. The catapult bolts and iron nails with their special heads are the main markers. What stands out here, compared to other sites of the same type and of the same period, is the abundance and the concentration of the armaments. Taking old discoveries and recent excavations together, more than 1260 arrowheads and a hundred horseshoes have been unearthed over an area of just 4000m2! The radiocarbon and archaeomagnetic datings are themselves all compatible with an attribution of the whole to the 1st century BC, more precisely to the Tene D2. Moreover, this occupation was obviously of short duration and of a very specific nature, judging by the thin layer containing the artefacts, the absence of significant furniture before or after the current of the building. 1st century and the concentration of objects in the military field. |

These different elements therefore lead to rejecting the hypothesis of a permanent habitat-type occupation in the area of the Loulié spring.

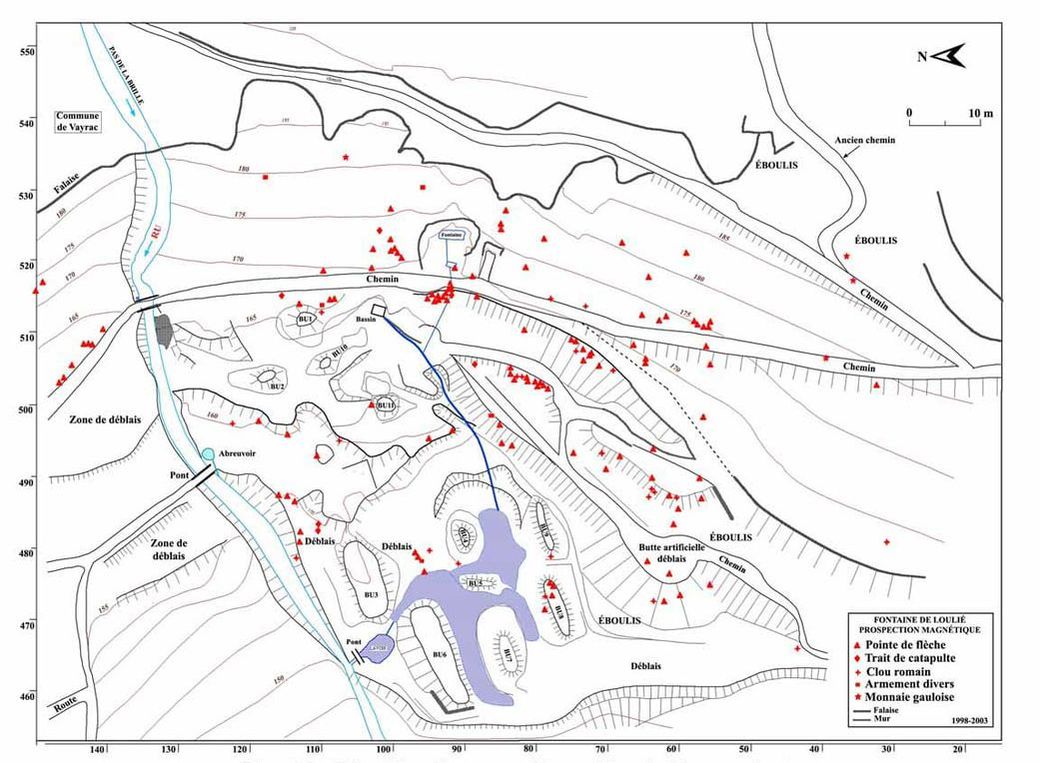

Electromagnetic prospection

This was the first work carried out in the field after a general clearing of vegetation and a topographic survey of almost 5000m2. Its primary goal was to save the site from systematic looting by unauthorised users of metal detectors which had been taking place for over 25 years. The information collected, compared to other studies, yielded a rich set of information.

This survey, authorised by the State, was conducted methodically around the Loulié spring, on the slopes, below and above the cliffs over a period of five years. Covering an area of almost 5000m2, it identified 1940 metal objects, including 112 arrowheads, 6 catapult bolts, a javelin socket, many sandal nails attributable to the Romans, three silver Gallic cross coins of which 2 are similar to one in the treasure of Cuzance (Lot) attributed to the Cadurques, a silver drachma with the triangular head of the Cadurques and 2 bronze coins of Lucterios. Of course, all the samples were mapped and no excavation of archaeological levels in place was made. Each object was referenced with its depth of burial, its position and the context of its provenance.

The arrowheads were found scattered on the slopes over an area of about 4000m2. They are totally absent at the foot or on top of the cliffs. The study of their distribution, allowed an outline definition of the limits of the battle, and informed us on the position of the Gallic defenses and on the possible implantation of the agger and the tower built by the Romans.

The results of this survey linked to those of the old and recent excavations confirm and supplement the report on the abundance of weapons on the site of the Loulié spring.

Note: 173 shoe nails attributed to the Romans were found during searches (Fig. 20). These nails, ignored by the nineteenth century researchers, are conical in shape, bear varying traces of wear on their heads. The shape of the pin, unique to this type of nail, held tightly one or more thicknesses of leather, each on average 6 mm thick. The end of the pin of some nails is bent twice in the direction of the head. The head was embedded in the leather, having the effect of holding the nail on the inner face of the shoe. By this reversal, the pin did not injure the legionnaire's foot. The peculiarity of these nails is to have a slightly hollow head and, under the head, geometric shapes in relief, such as ribs and small bumps. These reliefs were embedded into the leather of the shoe during nailing, and this probably prevented the nail from rotating. Caliga were shoes worn by Roman soldiers, including centurions, but not senior officers (3). This was a closed shoe, which entirely covered the foot; it had a thick sole, studded with nails (clavus caligaris) and was tied by straps which covered the instep and which surrounded the lower leg. They had about 80 to 90 nails (4). We find the same type of nails, with relief decorations on the reverse, in the Roman camps at Alesia.

Research on the tunnels

|

It is these underground structures that have attracted the attention of researchers and scholars since the nineteenth century, leading to the almost complete destruction of the archaeological levels in place.

It was therefore essential to resume work in this area as well, both to precisely locate the sections seen by the various past researchers (notably J.-B. Cessac, Napoleon III and A. Laurent-Bruzy), and to try to better understand the network, its purpose and its chronology. The research on these tunnels comprised many activities of different natures: successive soundings, manual clearing when they were found to be filled with earth, a complete topographic survey, a study of the way they were dug and analysis of the geological context. The clearing of sections already identified led to the discovery of new sections. From the stream, downstream of the site and quite low down the slope, a ditch was dug under the agger. In view of the Gauls, the Romans passed underground. The network rises steeply and bifurcates when it reaches the foot of the bed of travertine on the surface of which is the source. 1.5 m wide and 2 m high on average, these vaulted tunnels extend over a recognised length of 111 m (69 m for the southern branch and 42 m for the northern branch). |

From west to east lies the main G8 tunnel, partially discovered by A. Laurent-Bruzy in 1935, which seems to have divided in its upstream part into two longitudinal branches. One, to the south, was found in 1865 by J.-B. Cessac (G6). The other, to the north, includes sections G7, G1, G2, G3. Two upper tunnels G4 (14 m long) and G5 (length 8.40 m) were dug by the Gauls to intercept the Roman sappers (Fig. 16 and 17).

This very complex network of tunnels was the subject of an archaeological survey report by Jean-Claude Bessac (CNRS, UMR 154, Lattes) on digging techniques and strategies. According to this report, no tunnel discovered to date can be associated with stone quarrying, as much because of the very poor quality of the travertine as of the relative narrowness of the tunnels and their vaulted profile. In addition, the impacts of tools found on the walls do not correspond to those found in quarrying. The hypothesis of the capture of a spring by underground pipes to feed a mill or for any activity requiring abundant water cannot be excluded outright. However, no such installation was found downstream. But above all, it is hard to see why, in this hypothesis, two networks of tunnels would have been dug, a rectilinear one (north network) and the other broken (Cessac tunnel) and how to explain the two side tunnels G1 and G5. |

Moreover, according to J.-Cl. Bessac, the tunneling techniques correspond well with what we know of the techniques of Roman times. This information, together with the logic of the digging (the floor of the Cessac tunnel follows the surface of the impermeable black marl, starting downstream of the springs and going underground up to their level) leads us to consider that we are certainly in the presence of the Roman works aimed at drying up the springs down to which the Gauls came for their water supply during the siege of the oppidum.

The technical analysis of the G4 tunnel by J.-Cl. Bessac opens the hypothesis of a counter tunnel dug by the Gauls from upstream to downstream (5). In this case, the starting point of the collapsed G4 tunnel could be behind mound BU1 at the level of the communal path, directly above the red limestone cliff, with the digging of an open-air inclined plane (6).

|

The northern tunnel system did not enable the Roman sappers to find the black marl. Tunnel G3 seems to have been abandoned due to the difficulties of digging in unstable ground composed of soggy clay and sloping scree, but it is more likely to have been because of the Gallic counter tunnelling (tunnel G4). The G5 side tunnel could also be a counter tunnel to intercept the Romans at the Cessac tunnel. The tunnel abutted in gravel formed by repetitive action of frost on the rock and would not have allowed the Gauls to go further. According to J.-Cl. Bessac, the technical arguments in favour of a meeting of two teams of Roman sappers equally apply to a team of Gauls who would have worked in the G4 tunnel to try to stop the progress of the Romans. In this hypothesis, the G4 tunnel would become a counter tunnel and its annex G5 a research tunnel that would have been oriented to the south by the tool-cuts of the Roman sappers of G6 digging about 6 or 7 meters away. But the meeting between Gauls and Romans would have been faster in G3. To this hypothesis, one can consider in the first place Caesar's text in The Gallic Wars (in fact the editor Hirtius) which implies that the Gauls did not understand the Romans' tactics, and surrendered believing themselves abandoned by the gods after the drying up of the spring (7). The Romans often praised the strength and especially the bravery of the Gauls, because defeating them increased their own prestige. But they rarely applied this rule in terms of military intelligence, especially under the pen of Hirtius, who did not actually experience the siege. The affirmation of the Romans would only have served to demonstrate the intellectual inferiority of the Gauls. In the second place, it would also be necessary to explain the digging of the G1 tunnel by the Roman sappers. |

An initial explanation leads one to consider the additional drying up of secondary springs. But we can also consider a faster connection to tunnel G6, on the south side. The objective of the extension of G2 (beyond G1) and G3 tunnels by the Romans, who had certainly realised the low hydrogeological interest of the sector and the bad state of the ground, would have been then purely military - to divert the Gauls' attention and possibly confront them underground to allow time for the team of the south tunnel (G6) to finish their work. In addition, the desire to intercept the G5 sappers who dug 8 meters to the east, is not excluded. The hypothesis of a Gallic counter tunnel should therefore imply, in parallel, skirmishes, or even a fight in the tunnel G2-G3. No archaeological evidence attests to such military engagements (8), but the use of certain military devices, such as the use of smoke in tunnels, would leave almost no trace, especially in these places where the deposits of calcite quickly change the surface appearance of the rock. In favour of this last theory, we know that the use of counter tunneling is attested in antiquity (9). On the other hand, the hypothesis does not require the discovery of a junction between tunnels G6 and G4, since the Gauls were in their camp. They were able to dig a shaft for the descent to start digging the gallery in the area of their spring, even though they had to protect themselves from Roman fire during this operation. The presence in tunnel G4 of holes for hooks to support oil lamps does not seem to be a frequent Roman practice, but we do not know about the Gauls' practices. In Book VII of the The Gallic Wars, on the subject of Avaricum's defense, Caesar notes: "They (the Gauls) were crumbling our earth by digging counter tunnels, all the more knowledgeable in this art, as they have great iron mines and they know and employ all kinds of underground galleries."(10) We cannot therefore question the technical abilities of the Gauls in this area. |

The position of the agger and of the tower

|

There is no text that specifies the distance of the tower from the spring. It cannot exceed the range of effective shots by catapults, bows and slingshots. It must be far enough away so as not to be vulnerable, especially to flaming projectiles. From the tower alone, the Romans' projectile fire was not sufficient to be decisive. It did, however, greatly hamper the besieged who, exasperated, threw flaming barrels filled with tallow, pitch, and thin slats of wood (B.G., VIII, 42) from the travertine platform against the Roman construction. Hurtling down the slope to the bottom, they set fire to the mantelets (wooden protective shields) and the base. Simultaneously, the Gauls made an attack in force to absorb all the Roman forces, to stop them working to extinguish the fire. Caesar then gave the order that, on all sides, the troops should begin to climb the slopes and shout, as if they intended to cross the Gauls' fortifications (B.G., VIII, 43). The leaders of the Gauls recalled their combatants and placed them all over the walls. The fight having ended, the Roman legionaries were quick to put out the fire. It is surprising that the Roman troops were content to simulate an assault. Could they not have carried it out at this time or even much earlier? No doubt, but here as elsewhere, Caesar, anxious "never to sacrifice his soldiers of elite, rare and precious beings ... prefers a deadly escalation of a few minutes to the interminable fatigues of a blockade" (11). Frontin already explained that Caesar had adopted the medical motto: "Rather the diet than the scalpel" (12). Since the failed assault of Gergovie (B.G. VII, 47 sq.), Caesar, suspicious, halted before the slightest enemy fortification (B.G., VII, 69-70). The agger and the tower, as imagined by Jean-Baptiste Cessac, Napoleon III and Armand Viré, were at the foot of the travertine massif and, according to Etienne Castagné and other authors, on the platform of travertine. |

The tower was considered to be located at a distance of 20 to 30m from the Cessac spring, about 40 to 50m from the cliffs. This does not accord with the motives that led Caesar to use artillery to prevent the besieged Gauls from approaching the spring. The harassment of the Romans made the Gauls' access to the spring perilous. Taking water up onto the oppidum would have required a procession of water carriers from dusk until dawn in order to have the best security. Constructions put in place to protect these activities from attack would seem to be essential. These could have been walls and palisades, behind which the water carriers could shelter. If such a protective arrangement had not been constructed, access to the spring would have been severely disrupted by Roman fire from the tower. And a significant reduction in the water supply would also have shortened the length of the siege. But it was necessary to resort to capturing the spring by subterfuge, to remove access to this essential water supply. This proves that the Gauls in charge of fetching water were able to access the spring, bearing risks of course, but minimal risks. The contrary would have quickly brought an end to the siege. New research has shown that the Gallic basin discovered under Napoleon III was a simple natural cleft in the rock not known to the Gauls. The true basin would have been located about twenty meters further downstream, on the travertine platform, simply at the site of the primitive washhouse. The discoveries made on the south side of the site (in E20) show that the end of the agger, positioned by the former researchers, was located inside the Gauls' defenses. The shooting trials, carried out in 1998 and 2005 at the site of Loulié, using reconstituted weapons, made it possible to note that the tower was entirely in range of the enemy. |

Where was the tower ?

|

In 2005, surveys conducted downstream of the site by Hubert Camus (of Hypogée) as part of the geological and geomorphological study of the site, led him to consider that the limestone blocks and coarse gravel encountered in the surveys and brought to the surface during the storms of 2001 (?) and intersected in soundings could well represent the remains of the Roman agger or associated military infrastructure. Several characteristics distinguish them from the infra-travertine large block formation: they are not altered, they are packed in laminated clay sediments and not in an alteration clay, they are associated with a terrestrial malacofauna and an outbreak of fire in place dated to the final Tene (Calibrated age 195 BC to 1 BC). A resurgence of water between the stream and the house is in the axis of the main tunnel (Fig. 19). It already existed in the nineteenth century. It lies exactly in the axis of the main branch of the tunnels found by two soundings downstream and upstream of the house. The particularly minute excavation of the Gallic layers was the object, in addition to the classical coordinates, of a precise reading of the orientation and inclination of metallic objects (nail, arrowhead, catapult bolt). It was also noted whether the arrowhead or the catapult bolt was stuck in the ground. That is to say that the projectile had gone through at least 10 cm of the Gallic layer (floor of circulation or wasteland). We used only these objects to determine the origin of the shots. The orientations of the projectiles concerned were reported on the topographical plan of the site at 1/100th (13). |

The results gave as origin: 8 projectiles coming from parcel 176, and 4 projectiles coming from the stream and the house. Eight trajectories are 25 m wide from the edge of the current stream to the house. These results must be interpreted with great caution, because of potential errors: the object could have moved in the ground, its direction could be inaccurate due to its short length, as could its recording on the plan. Logically, but with reserve, we can position the agger and the tower north or north-west of the house. If one positions the tower between the stream and the house, the distance of the tower from the Gallic road would be of the order of 80m, it would overhang it by about 8 meters. If you fix the tower at the level of the road, you go back about 35m. It would overhang the path by about 4m. The limit of the shots would be on a radius of 115m from the tower. The maximum distance must not exceed the range of effective shots of catapults, bows and slingshots. The distance from the Gallic basin would be about 95 m. The inclination of the projectiles gives us an idea of the angle at which they were fired. Assuming that the tower overhung a few meters up the path of the water carriers up to the plateau, the angle of the shots ranged from 8° to 27°. For the two shots close to 50°, the archer sought a maximum range by taking a sighting angle of about 45°. The shooting experimentation carried out in 1998 and 2006 from the cliffs overlooking the Loulié fountain and the proposed site of the Roman tower, provided us with very useful information on range and the zones of insecurity and provided an understanding of the flight qualities of the projectiles and their effectiveness (Fig. 18). |

Conclusions

|

The work undertaken on the site of the fountain of Loulié over a period of 12 years leads to an updated reading of the question of the siege of Uxellodunum. First of all, the field data are now sufficiently numerous and consistent to confirm whether the interpretations of J.-B. Cessac and, in his wake, of Napoleon III concerning the location of Uxellodunum, were relevant. Field archeology shows us that the Loulié spring was indeed the theatre, around the middle of the 1st century BC, of a violent fight bringing together Roman troops against the Gauls. The abundance of armaments from the Caesarian period is impressive and unique in comparison with all the other battlegrounds of the same period identified in Gaul; this armament is clearly concentrated on the perimeter of the springs which obviously constituted the stake of the combats; the digging of underground tunnels obeys a logic directly related to the plan to dry up the springs; in this sector of Puy d'Issolud, the occupation of the second Iron Age seems tightly limited to the sector of the source and the period of the siege. |

Archeology has thus managed to recover most of the elements described or evoked by the text of Hirtius on the battle around the source of Uxellodunum: an abundant source of water located on the side of an elevated site powerfully defended by its natural characteristics, which was the scene of violent fighting and that the Roman troops dried up by digging underground tunnels. It is too rare for archeology to reveal so many obvious and concordant elements not to highlight it here. It should also be remembered that information from medieval texts and from toponymy are themselves in full agreement with the archaeological data. The aerial works built by the Roman troops to ensure the siege of the source (including agger) described by Hirtius cannot be sought where Napoleon III proposed to locate it. The hypothesis defended by Napoleon was indeed the following: the Gallic basin found in 1865 by J.-B. Cessac would be the source diverted by the Romans. It was allegedly defended mainly from the cliffs by rebels and archers. The Gauls from the "Pas de la Brille" would have descended, to fetch water, by two trails east and north-east of the source. |

However, it is obvious, from examination of the topography of the site, that these hypotheses raise some questions: defence of the site only from the cliffs could not have prevented the taking or poisoning of the spring; despite possible protection by a wall or a palissade, the descent from the "Pas de la Brille" to the spring seems difficult to imagine given the steep slope of the track.

This observation of this strategic difficulty leads us to consider a different scenario based on taking into account all the data from the ground:

This observation of this strategic difficulty leads us to consider a different scenario based on taking into account all the data from the ground:

- The water source found by Cessac is a natural overflow that has not been diverted. The water source to which the Gauls trapped on the oppidum of Uxellodunum came to refuel must be elsewhere: the most logical place for it is on the surface of the travertine mass, that is to say to fifteen meters at least from the Cessac basin and about ten meters below it; Obviously, it is this important water source that was the object of all the efforts of the Roman troops: it is in this sector that the highest concentration of Roman armaments has been found. And just below - and no further upstream - is the underground tunnel that dried up the small rivulets of water.

- The Gauls must have had access to this water source from the south-east, by a gently sloping path. The passage "Pas de la Brille" is without doubt a medieval path, that allowed the inhabitants of the Combe Nègre to replenish their drinking water supplies. About 100 m to the south-east, another very old path, forgotten for a long time, serves the terraces of the oppidum, propitious for human settlement. This hypothesis of access from the south-east is supported by the results of the electromagnetic prospection: it showed the absence of any arrowheads above the cliffs, on the top of the cliffs and on the north-east slope (between the overflow Cessac and the stream), and on the other hand, their strong concentration on the south and south-east sides of the site. Their mapping, in comparison with the objects discovered earlier, made it possible to define the combat zone and to confirm that the water source was indeed the epicenter. The arrowheads were scattered on the slopes over an area of about 4000m2.

- These observations confirm both the impossibility of a Gallic defense of the source from the plateau and suggest that it was necessarily organised from the source itself; moreover, this new topography of the battle implies that the Roman agger must be sought much lower down the slope than Napoleon III believed, at risk of positioning it on the source itself, a totally incoherent solution.

|

Two elements suggest the location of the imposing Roman terracing. The first is the mapping of the located weapons, including arrowheads and catapult bolts found in their primary position. This suggests a focal point from which shots were fired a short distance north of the current house west of the source, more than 50m below the position proposed by Napoleon. The second element is the presence of the main branch of the tunnels, in the form of a trench, which was found by two soundings (downstream and upstream of the house). Downstream of the house, a trial hole revealed a hollow structure with large rock blocks, attributable to final Tene (by the archaeological material) which could be a Roman construction linked to the agger. In another trial hole, at a depth of 1.10m, a large combustion zone containing rusted stones and charcoal was dated by radiocarbon to the final Tene. The excavation of a few shreds of archaeological layers preserved from the picks of the old researchers found the soil strongly reddened by the violent fire described in the nineteenth century. Under the action of fire, raw bricks (from Gallic defensive constructions) have cooked and taken a color ranging from pink to dark red, travertine blocks have been altered to become lime and building stones have been heavily reddened. The battlefield has delivered a large new batch of Gallic and Roman armaments, some Gallic pottery, charred wood pieces and fragments of Italian and Spanish wine amphorae. All the techniques used to date the use of this soil give the same results: the radiocarbon analyses of charred wood logs and paleomagnetic analyses of the sediments affected by the fire as well as the study of the objects, place the event towards the middle of the 1st century BC. The presence on this soil of a large number of oval pebbles weighing 50g to 2kg, from the bed of the Dordogne and therefore inevitably brought by man, suggests that they are projectiles. The smaller ones were able to be thrown with slingshots while the heavier ones could serve as ammunition for the ballistae used by the Roman troops. |

The resumption of the study of the underground tunnels has yielded key information, and has shown that only the Cessac tunnel has resulted in the capture of the water sources that fed the Gallic basin. However, despite the important investment of several years by a team with multiple skills, there are still outstanding questions: Hirtius evokes Uxellodunum as a stronghold of the Cardurques "remarkably defended by nature". However, to date, the mimimal archaeological research carried out on the plateau of Puy d'Issolud has provided little information about the Gallic occupation. The remains from this period are few in comparison to the abundance of those discovered in the sector of the Loulié spring. The plan of the fortifications proposed by Castagné would need to be validated, because the chronological argument proposed for the rampart is not solidly supported. It would also be interesting to look for the circumvallation which Caesar and his troops built around the site at the time of the siege and to look again at the question of the location of the three Roman camps established by Caninius and mentioned by Hirtius. Fabius and Calenus having subsequently brought four and a half legions must necessarily established other camps. These new camps were not built in preparatuon for a Gallic attack coming from outside, but with the single objective of investment. New excavations would verify and date these protohistoric fortifications and identify the nature and importance of occupation of the site at this time. The monographic publication of all the data from the old works and our own research is completed, the European Archaeological Center of Mont Beuvray, under the direction of Vincent Guichard was in charge of editing and publishing. The Uxellodunum Site Management Joint Syndicate (S.M.G.S.U), which was the prime contractor, was responsible for the development of the Loulié site. The purchase of the house below the site was carried out in 2009, the acquisition of the land, the restoration works of the galleries, the earthworks and the modeling of the site were carried out in 2010. |

Jean Pierre GIRAULT

Nota :

Nota :

- The drawings of the armaments and the plans were created with the collaboration of Pierre Billiant and Michel Carrière (archaeologists).

- The captions on the old photos are by Antoine Laurent-Bruzy.

Notes

- The majority of them could be shots launched by a ballista.

- The study of raw earth materials was carried out by Claire-Anne de CHAZELLES (CNRS, UMR 154, Lattes) with the collaboration of Handi GAZZA. The length of the bricks varies from 0.28 to 0.43 m, over a width of 0.19 to 0.22 m and a thickness of 0.14 to 0.17 m.

- Cic. Ad ATT. II, 3; Just. XXXVIII, 10; Juv. Sat. XVI, 24; Suet. Calig. 52. See Dictionary of Roman and Greek Antiquities. By Anthony Rich. Paris, Library of Firmin Didot, 1861.

- Junkelmann. - 1986, p. 158-161.

- The Gauls were perfectly familiar with mining work, which they used with great skill "in many circumstances, especially at the Avaricum headquarters (B.G., VII, 32)".

- The excavation of mound 1 revealed a collapsed construction composed of large limestone blocks that could be protection of the inclined plane allowing access to tunnel G4, and a layer of gravel reported on the Gallic soil could come from the digging of the inclined plane allowing access to G4 (the excavation determined that the earth brought back there corresponds to a displaced slope deposit). We also noticed, on the south side of mound 1, a variegated travertine sand deposit, which could have come from the digging of the tunnel G4.

- L. -A. Constans, Caesar, Guerre des Gaules, Paris, Hachette, 1961, p. 391.

- The presence of water during excavations did not allow the G3 section to be completely cleared. Between 0.30 to 0.40m of sediment remains at the bottom of the tunnel. Clearing tunnel G3 can only resume, for security reasons, once the restoration work has been completed. For the same reasons, the landslide between G2 and G3 was not completely cleared.

- Especially in Doura-Europos (Syria) where the Romans used this process against a Sassanid counter tunnel (see C. Hopkins, The Discovery of Dura-Europos, New Haven / London, Yale University Press, 1979, pp. 240-249). ;

- L.-A. Constans, Caesar, Guerre des Gauls, op. cit., p. 294.

- Jullian (C.) .- Histoire de la Gaule. T. III, p. 183.

- Frontin. - Stratag. , IV, 7.

- The grid of the excavated zones was postponed by the cabinet of experts surveyors Sotec-Plans de Brive.

Bibliography

Bouygues (Dr Maurice). - Le Puy d’Issolud est bien Uxellodunum. Limoges, Ducourtieux, 1914, in-8°, 106 p.

Buchsenschütz (Olivier) et Izac (Lionel). - L’habitat de l’Age du Fer dans le Quercy. Historique des recherches et perspectives actuelles. Aspect de l’Age du Fer dans le Sud du Massif Central. Actes du XXIe Colloque International de l’Association Française pour l’étude de l’Age du Fer, Conques - Montrozier - 6-2000, pp. 105-116.

Castagné (Etienne) :

- Rapport de la Commission des fouilles du Puy d’Issolud. Annuaire du Lot, 1866, pp. 17-29.

- Uxellodunum. Recherches faites à Capdenac, à Luzech et à Puy d’Issolud. Rapport de la commission des fouilles de Puy d’Issolud..... Annuaire du Lot, 1866.

- Mémoire sur les ouvrages de fortification des oppidums gaulois de Murcens, d’Uxellodunum (Puy d’Issolud) et de l’Impernal (Luzech) situés dans le département du Lot. Cong. arch. de France, Agen-Toulouse, 1874, pp. 427-538, avec plans et nombreuses illustrations. Tours, Bousrez, 1875, in-8°.

Cathala-Coture (Avocat au Parlement). - Histoire politique, ecclésiastique et littéraire du Quercy. Montauban, Pierre-Thomas Cazaméa, 1785, 3 vol., in-8°, (t. I, pp. 2-51 : le Quercy jusqu’à la conquête franque).

Champollion-Figeac (Jacques-Joseph)

- Examen topographique des lieux. Le Puy-d’Issolu, pp. 53 à 66, Luzech pp. 47 à 53, dans «Nouvelles recherches sur Uxellodunum».

- Nouvelles recherches sur la ville gauloise Uxellodunum assiégée et prise par J. César, rédigées d’après l’examen des lieux et des fouilles récentes et accompagnées de plans topographiques et de planches d’antiquités. Imprimerie Royale Paris, 1920,1 vol.,116 p., 6 pl.

Cessac (Jean-Baptiste) :

- A la bibliothèque de la Société Historique et Archéologique de Brive se trouvent les cahiers où Jean-Baptiste Cessac a consigné toutes ses recherches sur Uxellodunum, le déroulement des fouilles à la fontaine de Loulié, les correspondances diverses (notamment avec Napoléon III, le colonel Stoffel, le Préfet du Lot, les Ministres etc). Le dossier complet comprend plus de 1000 p. manuscrites.

- Etudes historiques, Uxellodunum, aperçus critiques touchant l’examen historique et topographique des lieux proposés pour représenter Uxellodunum, de MM. le Général Creuly et Alfred Jacobs. Extrait de la Rev. des Soc. Sav. des Départements, février 1860, Paris, E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, Palais-Royal, 1862, in-8°, 79 p.

- Etudes historiques Commentaires de César . Uxellodunum. Notices complémentaires touchant l’examen historique et topographique des lieux proposés pour représenter Uxellodunum. Paris, E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, Palais- Royal, 1862, in-8°, 31 p.

- Un dernier mot sur Uxellodunum. Paris, E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, Palais-Royal, 1863, 47 p.

- Mémoire sur les dernières fouilles d’Uxellodunum. Paris, Dentu, 1864.

- Notes sur les fouilles exécutées à Puy-d’Issolu. Rev. des Soc. Sav., 1866, pp. 464, 569-570.

- Le véritable emplacement d’Uxellodunum démontré aux moyens des fouilles. Manuscrit à la bibliothèque du Musée de l’Homme à Paris, daté de 1866, 14 p., 7 pl.

- Mémoire sur les dernières fouilles d’Uxellodunum, (Mémoire lu à la Sorbonne en 1866). Paris, Imp. Impériale, 1867, in-8°, 17 p.

- Le véritable emplacement d’Uxellodunum sous les auspices de la Soc. d’èmulation du Doubs. Comm. Rev. Soc. Sav., 1867, pp. 48-50.

Cessac (Jean-Baptiste), Bial (Paul), Lunet (Abbé). - A propos d’Uxellodunum. Congrès arch. de France, XXXII, 1865, pp. 437-440 et 443-450.

Constans (L.-A.). - César, Guerre des Gaules. Paris, Société d’Edition 'les Belles Lettres', t. III, livres V-VIII, 1981.

Creuly (le général) et Alfred Jacobs. - Examen hist. et topogr. des lieux proposés pour représenter Uxellodunum. Rev. des Soc. Savantes, Paris, Durand, 1860, III, 2 e série, pp. 182-217. - Reproduit dans l’annuaire du Lot, 1861.

Duruy (Victor). - Histoire des Romains depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu’à l’invasion des barbares. III, Paris, Librairie Hachette et Cie., 1900, p. 224. Autre édition Paris, Hachette, 1843-1879, 1881.

Frontin. - Stratagèmes de guerre (3,7,2).

Fouillac (L’Abbé Raymond de). - Dissertation sur Uxellodunum. Biblio. de Cahors, Fond Greil, III, p. 26 (XVII e siècle).

Girault (Jean-Pierre).

- Gaulois des pays de Garonne IIe et Ie siècle avant J.-C., Guide de l’exposition présenté au Musée Saint-Raymond - voir d’Uxellodunum au Puy d’Issolud le dernier combat, impri. Escourbiac S.A., 2004, pp. 73 à 85.

- Uxellodunum et la guerre des Gaules, Catalogue de l’exposition au Musée Labenche d’art et d’histoire à Brive-la-Gaillarde (Corrèze), du 15 juin au 30 octobre 2004, 24 p. et 2 plans.

- Les recherches au Puy d’Issolud 2000-2002. Premiers éléments des recherches sur la bataille d’Uxellodunum à la fontaine de Loulié, commune de Saint-Denis-lès-Martel (Lot). Annales des Rencontres Archéologiques de Saint-Céré, n° 11 2004, pp. 48 à 84.

- Les Ages du Fer dans le Sud-Ouest de la France. Recherches à la Fontaine de Loulié, Saint- Denis-lès-Martel (46). Nouveaux éléments sur la bataille d’Uxellodunum. XXVIIIe colloque de l’AFEAF, Toulouse, 20-23 mai 2004. Aquitania supplément 14/1, Bordeaux, mai 2007, p. 259-283.

Goudineau (Christian). - Regard sur la Gaule. édition Errance, mars 2000.

Guichard (Vincent). - Dossier - Guerre des Gaules - Uxellodunum, le dernier combat. L’Archéologue n° 60, juin-juillet 2002, pages 22 à 26.

Jullian (C.). - Histoire de la Gaule. Paris, Hachette, 1931, t.3, p.149, n. 1.

Lacoste (Guillaume). - Histoire générale de la province du Quercy. Publié par L. Combarieu et F. Cangardel, Cahors, J. Girma, 4 vol. 1883 ( I, p. 1-17) ; Réédition Paris, Guénégaud, 1968, avec notes complémentaires sur la période gallo-romaine par Labrousse (Michel), I, p. I-XXXIII.

Musée de Bibracte. - Sur les traces de César. Enquête archéologique sur les sites de la guerre des Gaules. Livret édité à l’occasion de l’exposition temporaire présentée au Musée de la Civilisation Celtique durant la saison estivale 2002. Fouilles au Puy d’Issolud, pages 14 et 15 et 25.

Napoléon III. - Histoire de Jules César. Paris, 1865-1866, 2 vol., Plans, (t. II, pp. 337-348 : campagne d’Uxellodunum et fouilles au Puy-d’Issolu à Loulié). Orose. - Histoire contre les païens. VI,II, 20-29.

Rambaud (M.). - L’Art de la Déformation Historique dans les Commentaires de César. Paris, Société d’édition 'les Belles Lettres', 1966, p. 7-8.

Rice Holmes (T.). - Caesar's Conquest of Gaul, appendice sur la Credibilty of Caesar's narrative. Londres, Macmillan, 1899, p. 173-244.

Viré (Armand). - Les oppida du Quercy et le siège d’Uxellodunum (51 av. J.-C.). Bull. de la Société des études du Lot, t. LVII, 1936, pp. 104-127, 412-427 et 552-570.Bibliographie

Buchsenschütz (Olivier) et Izac (Lionel). - L’habitat de l’Age du Fer dans le Quercy. Historique des recherches et perspectives actuelles. Aspect de l’Age du Fer dans le Sud du Massif Central. Actes du XXIe Colloque International de l’Association Française pour l’étude de l’Age du Fer, Conques - Montrozier - 6-2000, pp. 105-116.

Castagné (Etienne) :

- Rapport de la Commission des fouilles du Puy d’Issolud. Annuaire du Lot, 1866, pp. 17-29.

- Uxellodunum. Recherches faites à Capdenac, à Luzech et à Puy d’Issolud. Rapport de la commission des fouilles de Puy d’Issolud..... Annuaire du Lot, 1866.

- Mémoire sur les ouvrages de fortification des oppidums gaulois de Murcens, d’Uxellodunum (Puy d’Issolud) et de l’Impernal (Luzech) situés dans le département du Lot. Cong. arch. de France, Agen-Toulouse, 1874, pp. 427-538, avec plans et nombreuses illustrations. Tours, Bousrez, 1875, in-8°.

Cathala-Coture (Avocat au Parlement). - Histoire politique, ecclésiastique et littéraire du Quercy. Montauban, Pierre-Thomas Cazaméa, 1785, 3 vol., in-8°, (t. I, pp. 2-51 : le Quercy jusqu’à la conquête franque).

Champollion-Figeac (Jacques-Joseph)

- Examen topographique des lieux. Le Puy-d’Issolu, pp. 53 à 66, Luzech pp. 47 à 53, dans «Nouvelles recherches sur Uxellodunum».

- Nouvelles recherches sur la ville gauloise Uxellodunum assiégée et prise par J. César, rédigées d’après l’examen des lieux et des fouilles récentes et accompagnées de plans topographiques et de planches d’antiquités. Imprimerie Royale Paris, 1920,1 vol.,116 p., 6 pl.

Cessac (Jean-Baptiste) :

- A la bibliothèque de la Société Historique et Archéologique de Brive se trouvent les cahiers où Jean-Baptiste Cessac a consigné toutes ses recherches sur Uxellodunum, le déroulement des fouilles à la fontaine de Loulié, les correspondances diverses (notamment avec Napoléon III, le colonel Stoffel, le Préfet du Lot, les Ministres etc). Le dossier complet comprend plus de 1000 p. manuscrites.

- Etudes historiques, Uxellodunum, aperçus critiques touchant l’examen historique et topographique des lieux proposés pour représenter Uxellodunum, de MM. le Général Creuly et Alfred Jacobs. Extrait de la Rev. des Soc. Sav. des Départements, février 1860, Paris, E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, Palais-Royal, 1862, in-8°, 79 p.

- Etudes historiques Commentaires de César . Uxellodunum. Notices complémentaires touchant l’examen historique et topographique des lieux proposés pour représenter Uxellodunum. Paris, E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, Palais- Royal, 1862, in-8°, 31 p.

- Un dernier mot sur Uxellodunum. Paris, E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, Palais-Royal, 1863, 47 p.

- Mémoire sur les dernières fouilles d’Uxellodunum. Paris, Dentu, 1864.

- Notes sur les fouilles exécutées à Puy-d’Issolu. Rev. des Soc. Sav., 1866, pp. 464, 569-570.

- Le véritable emplacement d’Uxellodunum démontré aux moyens des fouilles. Manuscrit à la bibliothèque du Musée de l’Homme à Paris, daté de 1866, 14 p., 7 pl.

- Mémoire sur les dernières fouilles d’Uxellodunum, (Mémoire lu à la Sorbonne en 1866). Paris, Imp. Impériale, 1867, in-8°, 17 p.

- Le véritable emplacement d’Uxellodunum sous les auspices de la Soc. d’èmulation du Doubs. Comm. Rev. Soc. Sav., 1867, pp. 48-50.

Cessac (Jean-Baptiste), Bial (Paul), Lunet (Abbé). - A propos d’Uxellodunum. Congrès arch. de France, XXXII, 1865, pp. 437-440 et 443-450.

Constans (L.-A.). - César, Guerre des Gaules. Paris, Société d’Edition 'les Belles Lettres', t. III, livres V-VIII, 1981.

Creuly (le général) et Alfred Jacobs. - Examen hist. et topogr. des lieux proposés pour représenter Uxellodunum. Rev. des Soc. Savantes, Paris, Durand, 1860, III, 2 e série, pp. 182-217. - Reproduit dans l’annuaire du Lot, 1861.

Duruy (Victor). - Histoire des Romains depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu’à l’invasion des barbares. III, Paris, Librairie Hachette et Cie., 1900, p. 224. Autre édition Paris, Hachette, 1843-1879, 1881.

Frontin. - Stratagèmes de guerre (3,7,2).

Fouillac (L’Abbé Raymond de). - Dissertation sur Uxellodunum. Biblio. de Cahors, Fond Greil, III, p. 26 (XVII e siècle).

Girault (Jean-Pierre).

- Gaulois des pays de Garonne IIe et Ie siècle avant J.-C., Guide de l’exposition présenté au Musée Saint-Raymond - voir d’Uxellodunum au Puy d’Issolud le dernier combat, impri. Escourbiac S.A., 2004, pp. 73 à 85.

- Uxellodunum et la guerre des Gaules, Catalogue de l’exposition au Musée Labenche d’art et d’histoire à Brive-la-Gaillarde (Corrèze), du 15 juin au 30 octobre 2004, 24 p. et 2 plans.

- Les recherches au Puy d’Issolud 2000-2002. Premiers éléments des recherches sur la bataille d’Uxellodunum à la fontaine de Loulié, commune de Saint-Denis-lès-Martel (Lot). Annales des Rencontres Archéologiques de Saint-Céré, n° 11 2004, pp. 48 à 84.

- Les Ages du Fer dans le Sud-Ouest de la France. Recherches à la Fontaine de Loulié, Saint- Denis-lès-Martel (46). Nouveaux éléments sur la bataille d’Uxellodunum. XXVIIIe colloque de l’AFEAF, Toulouse, 20-23 mai 2004. Aquitania supplément 14/1, Bordeaux, mai 2007, p. 259-283.

Goudineau (Christian). - Regard sur la Gaule. édition Errance, mars 2000.

Guichard (Vincent). - Dossier - Guerre des Gaules - Uxellodunum, le dernier combat. L’Archéologue n° 60, juin-juillet 2002, pages 22 à 26.

Jullian (C.). - Histoire de la Gaule. Paris, Hachette, 1931, t.3, p.149, n. 1.

Lacoste (Guillaume). - Histoire générale de la province du Quercy. Publié par L. Combarieu et F. Cangardel, Cahors, J. Girma, 4 vol. 1883 ( I, p. 1-17) ; Réédition Paris, Guénégaud, 1968, avec notes complémentaires sur la période gallo-romaine par Labrousse (Michel), I, p. I-XXXIII.

Musée de Bibracte. - Sur les traces de César. Enquête archéologique sur les sites de la guerre des Gaules. Livret édité à l’occasion de l’exposition temporaire présentée au Musée de la Civilisation Celtique durant la saison estivale 2002. Fouilles au Puy d’Issolud, pages 14 et 15 et 25.

Napoléon III. - Histoire de Jules César. Paris, 1865-1866, 2 vol., Plans, (t. II, pp. 337-348 : campagne d’Uxellodunum et fouilles au Puy-d’Issolu à Loulié). Orose. - Histoire contre les païens. VI,II, 20-29.

Rambaud (M.). - L’Art de la Déformation Historique dans les Commentaires de César. Paris, Société d’édition 'les Belles Lettres', 1966, p. 7-8.

Rice Holmes (T.). - Caesar's Conquest of Gaul, appendice sur la Credibilty of Caesar's narrative. Londres, Macmillan, 1899, p. 173-244.