|

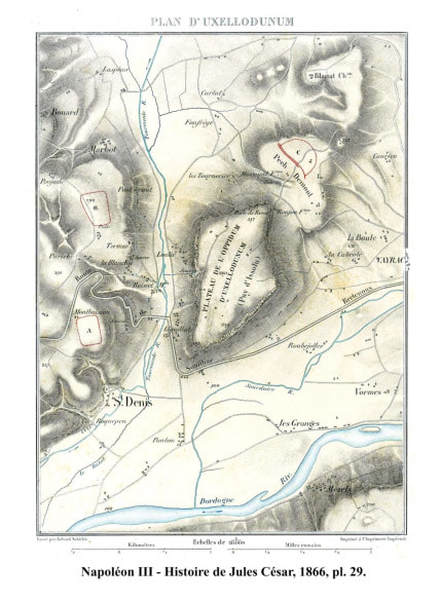

Puy d'Issolud, in the department of Lot, has long been known as one of the possible locations of Uxellodunum. Gallic troops in this stronghold, including survivors of Alesia, besieged by the legions of Caesar, delivered the last battle for the independence of Gaul. The plateau of Puy d'Issolud and its surroundings contain a large number of remains from prehistory to the Middle Ages. Puy d'Issolud is an geological outlier, separated from the Causse of Martel by the valley of the Tourmente and from the Causse of Gramat by the valley of the Dordogne. The plateau of approximately 80 hectares is situated mainly in the commune of Vayrac, with its western and south-western slopes in the commune of Saint-Denis-lès-Martel. Its highest point at 311m is in the north east, in the place called "Lous Templés". The plateau slopes down unevenly to the south-west to an altitude of 250m and, to the west, above the Loulié spring, to 210m. There are high, sheer limestone cliffs to the north-west and south. Elsewhere, the slopes and rocky outcrops are steep and often abrupt. |

To the north, a saddle joins Puy-d'Issolud to Pech-de-Mont (261m), the land sloping gently away on the north-west side towards the river Tourmente and to the south-east towards Vayrac. To the north-west and west of the plateau, the Tourmente crosses the plain of Viane, or the Hierle, (115 m), an ancient marshland today occupied by meadows, which extends to the village of Quatre-Routes. Despite regular drainage close to Saint-Michel-de-Bannières, this plain is flooded from time to time. Similarly, south of Puy d'Issolud, the Sourdoire Valley is frequently flooded as far as Bétaille. Before the construction of the railway line between the Tourmente and the bend of the Sourdoire, there was also a swampy and marshy area that prohibited any construction. When the waters of the Dordogne river are high, there is backflow into the waters of the Tourmente and the Sourdoire, which affects this old marshy area. |

The archeological context

The plateau of Puy-d'Issolud has been inhabited since the Middle Paleolithic. A number of vestiges of the late Bronze Age and of the end of the early Iron Age have been discovered there. On the other hand, the occupation of the second Iron Age is poorly known. In the 19th and 20th centuries respectively, Etienne Castagné (surveyor of the prefecture of Lot) and Armand Viré (Doctor of Sciences, historian, archeologist, speleologist and water diviner) described various earthworks and sizeable dry-stone walls which enclose the plateau at various points. These have been interpreted as being the remains of a rampart of this period, but no recent study has been able to confirm this interpretation or the dating. In the Tène III, in the second half of the second and the first centuries BC, a Gallic habitat that according to Armand Viré was surrounded by an enclosure with a wall and ditch is attested by houses whose bases were rectangular notches carved into the travertine. The walls of these wooden houses, were composed of interwoven wickerwork covered with clay. Many tools testify of the work of slaughter, carpentry (axes, adze, scissors), extraction (bars, wedges), earthworks (axes, picks), agriculture (forks, pruning knives). The presence of many cutlasses, punches or awls evoke the work of leather. Textile crafts, spinning and then weaving wool, are represented by the presence of spindles and weights. A metallurgical industry is attested by the discovery of a jeweller's anvil, chisels, iron slag and fragments of crucibles. The presence of domestic objects (forces, knives, grinding wheels, etc.), of indigenous common ceramics (baluster and cylindrical vases, shoulder-shaped pots and everted lips), amphoras and objects of adornment (buttons, fibulae, etc.) should be interpreted as evidence of habitats adjacent to artisanal areas. In the middle of the 1st century AD the Gallo-Romans were installed here. Finds dating from the end of the Merovingian era have also been recorded. At the end of the Merovingian period, the walls were restored, and a hideout (or castel) must have been been built on the site of a Gallo-Roman building that had probably been destroyed during barbarian invasions. The original archeological excavations at the Loulié spring had the single aim of finding the tunnels which were dug to capture the spring. No record of the strata was taken and the only observations at the time were made by Jean-Baptiste Cessac (Commissioner of Police in Paris), then by Armand Viré. |

During the course of these excavations many thousands of cubic metres of earth were moved by hand, using spades and pick-axes, without any sort of scientific observation taking place. These excavations brought to light finds from the area's occupation during the late Bronze Age and the two Iron Ages. Above all the most impressive aspect of these excavations is the remarkable number of arms from the epoch of Caesar which were found (among them more than 700 arrowheads, 75 catapult darts, six javelin tips and two lances). These finds confirm that this site was the theatre of a violent military encounter in the middle of the 1st century BC, and that the only explanation for the tunnels is that of a military construction with the aim of intercepting the spring. In addition, the considerable number of large deformed nails found in the midst of the remains of burned wood (the traces of a fire) over a confined area, indicates the possible presence of a large wooden structure. |

2020 © Tous droits réservés - Toute reproduction interdite sans l'autorisation de l'auteur.